Features

Business intelligence

Contracting

Fighting complacency

Practical ideas for preventing lacerations and crush injuries when handling flat glass.

February 13, 2013 By Colleen Cross

You’ve been handling glass for 20 years and you know what you’re doing.

You’ve done the same job, handled the same size of lites many times

before. You know what to expect. Right?

You’ve been handling glass for 20 years and you know what you’re doing. You’ve done the same job, handled the same size of lites many times before. You know what to expect. Right? Well, according to Mike Burk, your natural complacency puts you at risk for injury.

|

|

| When you handle glass every day, it is easy to forget how dangerous it can be. Mike Burk, chairman of IGMA’s Safety Awareness Council, recommends a four-step process for reinforcing safety in your shop.

|

Burk, product sales specialist for Quanex Building Products of Ohio and chairman of the Insulating Glass Manufacturers Alliance’s Glass Safety Awareness Council, presented a seminar at Win-Door last November that caught the attention of Glass Canada. In it, he laid out several case studies to a small audience and used a method of analysis worthy of a CSI to analyze them.

In his talk, Burk urges us to think IGMA. No, not the association – this IGMA is an acronym for four key safety points. He suggests those involved in fabricating and handling glass, in fact, anyone entering a plant, consider those four key letters – whenever faced with a task or situation: I (instruct), G (gear), M (move) and A (attitude). Instruct – Do workers know their risks, and do they have, and follow, clear instructions on weight limits and procedures? Gear – Do workers have, wear and maintain the appropriate PPE and equipment? Move – Do workers move deliberately and safely, always considering their surroundings, and giving themselves an escape route should something go wrong? Attitude – Do management and workers share safety as a priority, and fight complacency in the workplace?

Although it’s not possible to expect the unexpected, says Burk, by viewing situations, including past incidents and near misses, through this special lens, he thinks we can learn to recognize and prevent dangerous situations.

APPLYING THE IGMA METHOD: A CASE STUDY

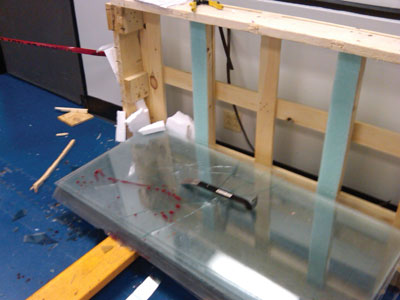

Burk thinks case studies can provide invaluable clues to prevention. Consider this WorkSafe BC case study in which a worker in a glass and window installation shop had his neck lacerated and his ribs broken.

“Large sheets of glass (3/8 inch thick, 34 inches by 80 inches) were sitting in an A-frame cradle. A young worker tipped several of the sheets toward himself so that a second worker could access sheets deeper in the stack. As more sheets were tipped forward, the increasing weight of the stack caused the worker to fall back against a work table. The falling glass sliced the worker’s neck, and the impact of hitting the table broke several ribs.”

Analyzing the incident using the IGMA approach, Burk suggests, draws out the pertinent issues:

- Instruct – Were workers aware they had other options? They shouldn’t take shortcuts, Burk says, but instead use whatever equipment is available to them to secure the glass.

- Gear – Was the worker wearing proper neck protection, such as a turtleneck-style dickey?

- Move – Was the glass secured so that even if it did shift, it wouldn’t fall on the worker?

- Attitude – Burk says some workers have the habit of leaning one glass sheet in a pile forward to hold it while another person retrieves another sheet from farther inside the pile. This situation, he says, can be very dangerous, because as the glass moves, its centre of gravity shifts, throwing the worker off balance.

INSTRUCT

Do workers know their risks? Do they have, and follow, clear instructions on weight limits and procedures?

Assess your risks – Burk recommends employers develop a template to identify tasks, calculate the risks they involve and determine how to prevent injury by way of asking questions and observing workers.

However, he notes that risk assessment only goes so far when you’re looking at safety, because you can’t always anticipate problems.

“A hazard identification and risk-assessment process is really the cornerstone of any health and safety program, and what that does is enables the workplace to be proactive in trying to solve these issues,” says Dhananjai Borwanker, a technical specialist with the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety.

Set and post clear guidelines – Borwanker says employees, too, have a responsibility to consistently follow guidelines to minimize the dangers.

These guidelines, says Burk, may include instructions from supervisors on how to dispose of glass when making trim cuts; for example, rules about breaking the cuts into smaller pieces or just lightly tapping the glass into the bin to prevent shards from flying through the air, and instructions about bagging discarded glass separately and labelling it. Such instructions help workers by taking the guesswork out of the process.

Learn from case studies – Burk says small group meetings can be helpful in creating an atmosphere of problem solving and prevention. He suggests employers use case studies and analyze near misses. He has found this last approach very effective. Sometimes it’s easier to talk about mistakes that were made when no one has been injured, he notes. However, realizing how close they came to injury creates a sense of urgency about solving the problem.

He cites “Measuring Safety Excellence: A Practical Framework,” by Shawn M. Galloway for Occupational Health & Safety Online, who takes the approach that we should begin with the end in mind when reviewing incidents.

“Being in the United States at the time of the London 2012 Olympics, the results are known hours before the events are broadcasted,” writes Galloway. “Viewers know who won prior to watching their performance. This vantage point moves the viewer beyond results to understanding what performance contributed to it. We must think the same way with our safety measurement systems.”

Know your weights – Knowing the weights of the lites you’re handling can prevent all-too-prevalent crush injuries, says Burk in his presentation. He urges employers to have clearly defined instructions on the maximum weight one human can safely lift, the minimum weight that requires two people, and the minimum weight that requires the use of mechanical assistance. According to GANA Glass Information Bulletin 01-0408, “Glass weighs approximately 2,531 kg/m3, or 158 lbs/ft3. A 3.0 mm, or 1/8" glass weighs 7.6 kg/m2, or 1.6 lbs/ft2.” The translucent appearance of glass is deceptive, warns Burk, who uses the example of a bowling ball to drive home how dense and heavy the substance is. “A standard bowling ball, with 27-inch circumference, usually weighs 12 to 16 pounds,” he says. “A bowling ball made of glass weighs about 30 pounds, so it’s almost twice as heavy.”

Only by knowing how much lites weigh can workers estimate, how the centre of gravity might shift when a lite moves or falls, says Burk.

GEAR

Do workers have, wear and maintain the appropriate PPE and equipment? The ASTM E2875/E2875M, Guide for Personal Protective Equipment for the Handling of Flat Glass, covers safety equipment requirements.

Know body’s four critical areas – Are all workers aware of the four most critical locations on the body?

Burk reminds us that cuts to the wrist, neck, underarm and inner leg are most likely to be fatal because those involve main arteries, and may result in almost instant death. He also points out that hand injuries, though not usually fatal, appear to be the highest occurrence among workers; thus, special attention should be paid to choosing and wearing proper gloves with adequate cut resistance.

Workers should have access to, and for their part, never fail to wear, the appropriate personal protective equipment for each of these areas. “For a long time people didn’t wear neck protection at all,” he says, “but it is critical.” Aprons provide inner-leg protection and riveted grommets provide underarm protection.

Supervisors must instruct employees – in particular, installers, who tend to be less well prepared than manufacturers – on when and how to wear the equipment and how to know when it needs replacing.

Ray Wakefield, manager of technical services at Trulite Industries in Vaughan, Ont., and former president of the IGMA, says his company stepped up safety measures more than a year ago, with positive results. “I would say yes, there’s been an improvement in safety,” says Wakefield, “but I can’t back it up with numbers.

“What we introduced was a Kevlar shirt, with long sleeves and a mock turtleneck, so that it does protect workers around the neck more than just having arm guards and a vest with only a t-shirt underneath, in addition to the standard hard hat, safety glasses and safety boots,” Wakefield says. “And that is something that they all wear, including supervisory personnel that are in the plant. You get better buy-in when supervisors wear them to – and they do.”

The shirt is readily available, if “not cheap,” says Wakefield. A great feature of this shirt is that its distinctive orange colour and grey sleeves stand out in a large plant. “A guy could be a hundred yards away and if he’s not wearing his shirt, you see it.”

Cut protection and resistance – In preventing laceration injuries, it’s important for management and employees to understand the difference between cut protection and cut resistance.

Most workplaces have strong cut protection, which involves many elements: PPE, machine guarding, training, equipment layout, handling equipment. But, while there is a lot of gear out there, not all of it is cut resistant,” Burk says. “Cut resistance is the ability of the material to resist damage from a moving, sharp object. Make sure that the cut resistance is adequate for the job.”

The ASTM F1790/ISO 13997 evaluation standard for North America, has a cut, or rating, force scale from 0 to 5, and a Cut Protection Performance Test for cut resistance only, not puncture resistance – 0 means an object will slice right through it, 5 means 3,500 grams will be resisted. Burk says most workplaces require a rating of 4 or 5, depending on the particular job.

The European standard is CEN EN388, and the two are not interchangeable. EN388 offers a Cut Index that measures resistance, puncture, tear and abrasion: the number of cuts it takes to break through the material. The scale here is 0 to 5 as well, with 5 the equivalent of 20 cuts to break through.

Protection can take many forms, he concludes on the subject, but resistance is crucial.

Use proper handling equipment and inspect it regularly – Burk says it’s important that supervisors have proper and well-maintained handling equipment available, and that workers use it. Workers have access to useful tools and equipment, he says, but sometimes take shortcuts, feeling they don’t have time to use it. “You’ve got to set rules about when they can do that, and when they need to use the equipment,” he cautions.

Slot racks are sometimes overloaded, and loaded with lites that are much too tall for their size. A-frames and L-racks also can be overloaded very easily, with the added danger that they are on wheels, meaning a bump or imperfection in the floor can upset an entire rack and cause a worker to be crushed. Ask yourself, “How much can this [rack] hold safely,” says Burk, and “develop rules and regulations for its use.”

Inspect this and other equipment regularly. “Ties and straps, carts and racks, hoists and lifts, all need to be in good working order,” he says. As an example, many ties wrap around raw edges and are heavily worn over time; thus, they must be inspected and the inspection recorded. Suction cups must be clean, demonstrate good suction, and be in the correct position. Lastly, wheels and casters bear a lot of weight, and shatter stops must be in place in case they cannot handle that weight, advises Burk.

MOVE

Do workers move deliberately and safely, always considering their surroundings, and giving themselves an escape route should something go wrong?

Burk suggests we consider movement on two levels: are we moving safely, slowly, and methodically, and are our surroundings conducive to safety?

When workers take shortcuts to save time, they open themselves up to injury by skipping key steps and precautions. Management can play a role in preventing such incidents, he says, by allowing workers adequate time to carry out tasks.

Is there any object that might obstruct our movement? Are floors even and dry? Are we working at an unfamiliar site? If a lite falls unexpectedly, do we have in mind a clear route of escape and do we have room to escape?

Having clearly expressed rules and procedures is important, but do we know what to do when things go wrong? By assessing situations, especially those that involve a new worksite or unfamiliar elements, using IGMA or any other method, we can identify potential problem scenarios and create contingency plans.

Burk’s video, Glass Handling Safety, taken from his MyGlassClass online safety course, offers a good example of setting up an escape route. As demonstrated in the video, escaping can be as simple as two people, who are carrying a large lite vertically, standing on the same side of the glass and holding it firmly with their bottom hands turned outward, so that the glass will naturally fall away from them. You can find the short video by searching “glass handling safety” on YouTube.

ATTITUDE

Do management and workers share safety as a priority, and fight complacency in the workplace?

Early on in his Win-Door presentation Burk cautions against complacency: “We get comfortable,” he says. “We let down our guard. We are not always aware. We don’t always watch and warn our co-workers.”

Although intangible, attitude is a very important element of safety for him. To sum it up, in an ideal world, employers and employees both see safety as a priority.

Employers should impress upon employees the danger of the work they are doing, says Burk, and they must do more than pay lip service to employees when dealing with their concerns if they want to have their trust.

For their part, says Burk, workers should watch out for fellow employees, let them know when they are doing something wrong and correct them if possible. “Don’t be afraid to report an incident or violation,” he says. “You might be the next one to get hurt.” This is especially important, he adds, when working with more vulnerable workers, such as those who are young, inexperienced, or who have a language barrier and may find it difficult to understand and follow rules.

The most significant bad habit Burk has observed says more about an attitude of complacency than gear: people not bothering to use their equipment. He says this is sometimes the case with management, who are just entering a plant for a moment to check something, and don’t take the time to wear proper PPE.

Burk’s favourite example of complacency is the skilled, experienced and well-equipped kayaker who is approached from behind, and beneath the water’s surface, by a shark. “I can’t say it enough,” he says. “Don’t get comfortable. Don’t ever let down your guard. Always stay aware. Watch and warn your co-workers.”

Safety tips from CCOHS

Although you can’t anticipate every situation, says Dhanaraj Borwanker of the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, there are a few things you can do to prevent dangerous situations and injury:

- Don’t try to catch falling glass.

- Store glass in dry conditions.

- Maintain and inspect your equipment before use, especially if you’re going to a different site.

- Make sure floors are level. That’s really important when you’re going to a new worksite. Make sure not only that the floor is level but also that it can handle the weight you’re putting on it.

- If there are windy conditions, tie the glass down.

- Keep glass that you’re taking to a worksite out of the way of other workers and find a place where it will be safe while you’re doing your tasks.

- Wherever possible, use mechanical aids to lift and move the glass itself.

Print this page

Leave a Reply